A short, romantic vignette of my current reality:

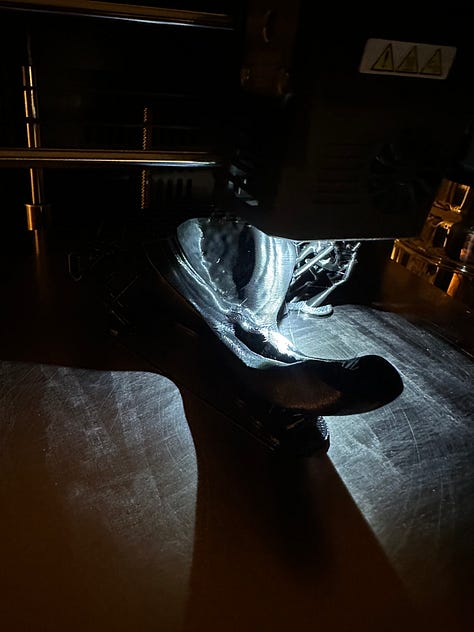

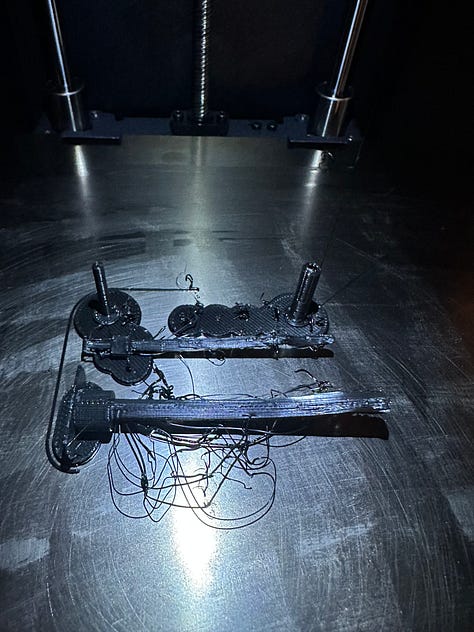

The 3D printer hums on my kitchen counter next to a large stainless steel sink. Its precise movements shape another piece of anatomy; today, it’s a uterus. This thick-walled, hollow form emerges layer by meticulous layer from the spool of black, satiny filament. Yesterday, it was a series of clitoral forms, each a different version of the same structure, function, and presence. My conceptual dissection and material reconstruction is a reimagining of what these organs could mean when removed from their biological and cultural contexts.

It’s been snowing for two days non-stop—the real novelty for me. The world has quickly muted to monochrome. My kitchen has become womb-like itself, where experiments take on a life of their own while I slowly refamiliarize myself with this feeling of hibernation. I haven’t actually experienced a real winter for three years, having travelled between Australia and Maui repeatedly. The printer doesn’t care about the season, though—it works with cold precision, unbothered, translating gcode into tangible forms. Prototypes of reproductive organs sit next to my warm cup of tea. This overlap of the personal and the experimental is where I feel most at home—in spaces where the intimacy of the everyday meets the provocation of messy biology.

I sip my nettle broth, obsessively watching the unfinished uterus take shape on the printer bed. It’s remarkably precise, clinical almost, mesmerizing. Each pass of the print head adds a fraction of a millimetre to the structure, making me think of the slowness of biological growth. I’ve learned patience with process through repetition of so many lab experiments, watching cells self-assemble as they are also biochemically programmed to do. Soon, I’ll hack this machine into a bioprinter, swapping filament for my concocted bioinks and testing these forms with live cells and tissues. What happens when we remake the body in compartmentalized pieces? What would it mean to hold a uterus grown from my own cells? Would I feel motherly or protective towards this symbol of reproduction? Would growing it on my own kitchen counter feel too precarious? Or does its remove from the whole organism render it somehow affectively colder?

Side note: The question feels less abstract than it should. I once kept my placenta in my mother’s freezer for nearly a decade. She finally threatened to feed it to her roommate if I didn’t deal with it. That organ was once the binding cable between myself and my child—an alien piece of me that had fulfilled a biological purpose but fascinated with its anatomy, I couldn’t bring myself to just trash it. I wonder if I’ll feel the same about these prototypes, once they’ve taken on the fragile qualities of living tissue.

My counter, despite my best efforts to stay on top of my creative mess, is cluttered with spools of filament, stiffened paint brushes, specks of copper leaf, stray tools, sketches on olive oil-stained paper. It’s an unintentional archive of a space that’s been mutating—part kitchen, part studio, part lab. Sterile winter light angles across the counter, catching the edges of the prototypes, the curves of the unfinished uterus. I’m enamoured with the matte dark sheen of the e-PLA filament once it’s shaped these organs. It imbues them with something akin to a kink aesthetic. Gynecological kink, where clinical precision meets taboo? It’s an unexpected aesthetic, transcending the plasticy-ness of the material. I didn’t know I could find something as banal and biologically threatening as plastic so alluring. I suppose aesthetic surprise is part of this process, too—how a material I’ve always dismissed as inert and unfeeling could take on such a provocative presence.

I’ve also printed an anatomical penis, life-sized, to study the structural parallels it shares with the clitoris—the same foundational form, but scaled and shaped differently, an enlarged mutation. Both these organs are developed through the same embryonic pathways yet assigned divergent cultural and physiological roles. In my kitchen, stripped of their organic context and rendered in black filament, they become objects of study rather than identity—detached from gender or reproductive expectations. However, printing these forms has also instigated an examination of my own relationship with anatomy. The act of creating them: slicing the model, watching them emerge layer by layer feels oddly intimate, even voyeuristic. I can almost project sensation onto them, and it returns back to my own body (thanks, mirror neurons!). It’s somewhat disorienting, a weird combination of detachment and connection. As I watch the print head trace each line, I think about the delicate interplay of nerves, blood vessels, and tissues these prototypes represent. Holding a finished piece is no less intimate. The plastic cools quickly in my hands once I’ve dismounted it from the print bed plate, but my mind overlays the warmth and texture of skin. These forms are not alive, but they are evocative.

Today I’ll head back to the university lab, to begin to assemble a clone motherboard that I’ll need to adapt the printer to extrude from a syringe full of viscous gels and cells. This is where theoretical will merge with tangible, and the precision of the machine will interact with the chaos of biology. The black sheen of plastic kink will soon give way to glistening textures of bioengineered tissues. This unfolding, in the collision of everyday routine and speculative inquiry, feels less like a straightforward project and more like an exploration of edges. The prototypes on my counter pose questions, imagining new boundaries of biology, technology, and meaning. As the relentless snow outside continues to insulate my kitchen-lab space, I’m reminded that the act of making—whether with plastic or cells—is sensual and generative, in its navigation through discomfort and ambiguity.