Blood, interrupted.

Research notes and observations from the Institute of Molecular Medicine, uLisboa in partnership with Cultivamos Cultura.

Dear friends, this post comes to you upon my return to Canada—for the first time in two years. I have very mixed feelings about revisiting my ‘home’ country but I’m excited to be heading to Windsor next week for the FEMeeting 2024 conference. I’ll be surrounded by an abundance of fabulous women and femmes working in art, science and technology and will present my most recent work, the Pussification of Biotech. This is a long-term project I’ve been developing collaboratively with Jiabao Li, including the work I’ve done while in Lisbon the past two months as part of my Cultivamos Cultura/ Ectopia residency. In preparation for the FEMeeting event, while I formulate my presentation points, I want to share some interesting speculations, observations and juicy results from my laboratory experimentation at the Institute of Molecular Medicine (iMM), uLisboa.

Before being authorized to commence any experiments at the iMM, I was required to provide proof of vaccination for Hepatitis B (HBV), a blood borne pathogen. I had never been vaccinated for HBV, meaning I had to make it happen quickly so that none of my short residency period was wasted. My research depends entirely on my menstrual cycle and the window for that is also very brief, with only two or three sample collection days per month, within the first few days of bleeding. I had one chance to collect samples at the start of my residency so that I could actually do my work, and then another chance midway through as backup if my first experiments failed.

To add urgency to the situation, I menstruated within the first week of arrival, meaning I had to start collecting my samples before I’d been vaccinated or authorized. The real urgency was in getting the samples into the lab while the stem cells in the blood were still viable (within a couple of days). My hosts, Marta and Luis were like wizards, immediately putting the vaccination process in motion and two days later I was vaccinated. This meant that I was vaccinated while menstruating, so had collected samples for two days preceding, and then I collected another one post-vax. Thus, I had before/ after vaccination samples and cultured both, in two separate flasks.

Being vaccinated mid-cycle complicated things for my project. The vaccine experience itself was fine, but my menstrual cells cultured from the ‘post-vax’ sample were not. The flask of cells from the ‘pre-vax’ sample thrived, growing prolifically. The ‘post-vax’ flask of cells failed to thrive, expiring quickly. There could be many reasons for this, some having nothing at all to do with the vaccine. Cells cultured in vitro can be finicky; things like temperature (or even weather) differences, freshness of the nutrient medium, contaminants, donor diet or other health factors, etc. can all affect the activity of the cells—those taken directly from a donor, versus standardized cell lines prepared by a lab supply company, can understandably be more volatile. However, it is also feasible that the vaccine could have impacted cell viability since both flasks were cultured under identical conditions and at the same time. I don’t understand the mechanisms for why vaccination may do this because I’m not an immunologist (and even immunologists I spoke to had no idea, because the uterus is under-researched), but I do know these things: 1) uterine function via menstruation is considered a vital indicator of immune function;1 2) previous vaccinations impacted my uterine function by delaying menstruation significantly and/or changing the quantity of bleeding that occurred.2 Important to note is that my menstrual cycle regulated itself to within normal range the following month after each vaccination.

In the lab, I was happy to at least have pre-vax samples thriving so that I could first build up a population for cryo-preservation (also as backup). This is a critical step in working with primary cell cultures, since sample acquisition is sporadic and numerous things can occur that compromise the cultures. After a full month of culturing my endometrial tissue fragments into adequate cell populations, and as I prepared them for cryo, I experienced a contamination event caused by another lab researcher. This meant that all of my cells were compromised. Regardless, I still had another period due in short order, so not all was lost… or so I thought.

Unfortunately, my period (typically operating like clockwork) didn’t arrive on time. Without controlled evidence, I can’t say for sure that this was caused by the Hep B vaccine, but based on my previous post-vax menstrual experiences and the existing science (and the possibility that my cells were affected), I can speculate on the likelihood that my cycle was dramatically delayed due to vaccination. Typically, I wouldn’t be overly concerned, since as I mentioned, my cycle regulates itself within a month. However, I didn’t have another month in Lisbon, so I began to stress hard—such are the perils of relying on your own body for research, and expecting a cooperative uterus that always churns out material.

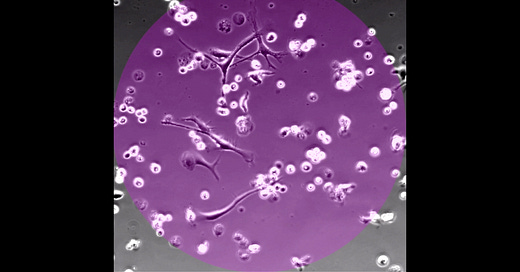

In the days leading to my imminent departure from Lisbon, I made a last attempt at live cell microscopic imaging—I’d had two sessions already that didn’t show me what I’d been hoping to see: stem cell differentiation to neuronal types. My entire research proposal was to develop new protocols specifically for producing neurons from period blood, basically. With this final push, I was using a new set of growth factors to stimulate cell differentiation—to hopefully capture the transition from stem cell to something resembling features of a neuron. The contamination was an aside—I still used the cells even if compromised, because I had no other option.

This last session, which I’d booked weeks in advance, was a one-shot deal: the imaging would run for 72 hours and conclude the day before I was leaving. I’d borrowed the growth factors from an associate neuro lab, so the amounts weren’t exact (inaccurate ratios) but I had to go with it and hope for the best—I was there to experiment, after all. When I checked on the progress of my cells after 24 hours, they were all dead. The microscopy was apparently a bust. The likeliest explanation was that the cytotoxic dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) that the biochemicals had been dissolved in to create the growth factor solutions was too high in quantity and killed my cells.

What followed is something I can only characterize as a rare synchronous opportunity, what some may call a miracle. With only two days left before my flight from Lisbon, and after an almost three week delay, my uterus gifted me with a thin red ribbon of stem cell juice—the slow beginnings of a new period. I poured the scant contents of my menstrual cup into a sample tube and transported it immediately to the lab, where I deposited the live cells directly into a new microscopy slide chamber (called a ‘well’)—something I’ve never done, for numerous reasons that make it less than ideal. Since I wouldn’t have time to grow a full flask of the cells (which requires fetal calf serum and basic growth medium), it meant they went directly into the differentiation medium (serum-free), an approach I’d never tried before.3 Off to the microscopy suite I went with my new samples, to replace the dead slide and use up the rest of my booked session, with the tiny hope that something interesting might happen.

Tiny hope became pretty big results. When I returned to see the imaging captured over the remaining 40-ish hours, I was elated. Not only were the new cells performing robustly in the fresh differentiation medium I’d prepared (without DMSO), some also demonstrated dendrite formation, including both radial branching extensions and triangulated lengths (almost axonal), that indicate neuronal formation. I gathered my data and left the lab feeling the glow of salvation—I had a new protocol, and the evidence that it probably works. Next day, external hard drives clutched in hand, I boarded my plane back to Canada.

Here’s a private link to the full 1:30 minute video (with audio) of the very excited cells in action, moving around, transmogrifying and communicating with one another about it—for my paid subscribers:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Frantic Panties to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.