The Future is Fluid

DIY 3D bio-printing at home, the flower moon, obscene omissions, and an artist doing a postdoc, WTF?

At night as I lay in bed, I am inundated with the heady waft of blooms. I thought at first that I was experiencing phantosmia,1 because I couldn’t locate the source; I’d closed my window against the city’s barking dogs, raving drunkards, and sirens. A sort of odor sānctitātis permeated my sensory sphere, a smell close to death, that of sticky lilies, only slightly more peppery. What beatification was unwittingly taking place?

I discovered that my bedroom snake plant had flowered prolifically (and continues to flower), with whiskery, white stars. The first night, they imbued my sleepy sanctuary with a miasma of almost sickening, potent perfume that would not let me sleep. This nocturnal oxygenator releases its urgent scent to compel its shady lovers, dusky pollinators, into dark revelry. By sunrise, its grasp has faded, as dreams.

Meanwhile, outdoor blossoms have exploded onto sidewalks, littering petals to be trampled underfoot or swirled in eddies of warm air at the curb. The magnolia trees are particularly magnificent, letting go of the tight buds of potential they held close, seeking beauty in release. This florid life/death nexus drips its metaphors into my current transitional state, lessons of the recent Scorpio full moon (or, flower moon).

My new postdoctoral research fellowship at Simon Fraser University’s School of Interactive Arts & Technology officially began the first of this month. The closure of one chapter (PhD) and start of something new is a vulnerable step over the next threshold of my career, and one I weighed very carefully before taking. My decision-making was strategic, building towards a precisely rendered vision of what I desired my future to become. Exciting opportunities have unfurled in front of me already—some of which I’ll share further on, speaking of desire. The future is fluid, as always. I will extend an invitation to you at the end of the post.

One may be forgiven for wondering WTF an artist is doing in a postdoc position. Like, why not just make art? Indeed, this is a question I am addressing as part of my research activities:

Working with and developing new tissue engineering protocols as part of my bioartistic method creates distinct institutional dependencies: I am unable to order specialized reagents (prepared liquids) and other restricted materials I need unless I do it through a certified institutional lab—complete with its labyrinthine ordering systems and other layers of accounting bureaucracy.2 I am also dependent on expensive equipment suites required to conduct scientific experimentation processes and to maintain the viability of my materials (live cells). Cell culture and tissue engineering remain closely guarded practices for these and other reasons: legislative policies around environmental and biohazard controls, entrenched knowledge hierarchies within institutional disciplinary boundaries, and as I (and my mentors and colleagues) have encountered, sometimes virulent cultural backlash. In other words, risk management vectors determined across governmental, industrial, institutional, and social interests.

But, artists are supposed to take risks.

In my case, risk-taking involves pushing the limitations of my materials to instigate intellectual and emotional tensions, but also to budge the boundaries of bureaucracy, nudging for allowances that might lead to more autonomy (as a feminist urge). I do this with full appreciation of the privileges conferred through institutional affiliation, but I’m also interested in understanding the enmeshed levels of restrictions placed upon me. What assumptions about who is entitled to fabricate ‘life’ are embedded in these access protocols?3

I am both within and more often than not, sidelined by the institutions I work through. As an artist who once jumped the electric fence around a restricted field, being institutionally affiliated (however loosely) is now necessary to my art making. As a postdoc, I’m specifically attempting to soften the barriers to doing the kind of work that I do, through Feminist DIYbio and Kitchen Science.4

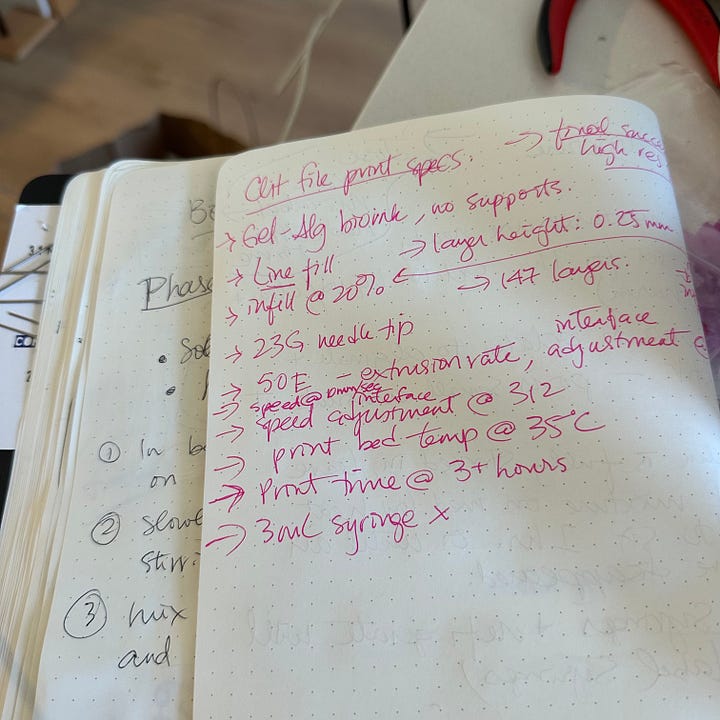

I began building (hacking) my own lab equipment in 2014, to have greater access and agency in carrying out my tissue engineering projects. Even though I continuously performed excessive bureaucratic rites, my backdoor pass to specialized biolabs was still limited. Part of the reason was that very few (and when I say few, I mean possibly three artists in all of Canada) had done, or were doing, work with tissue culture. My first device was a CO2 incubator controlled with Arduino.5 I equipped it with a small Erlenmeyer (conical) flask system made into a bioreactor and nutrient fluid receptacle hooked up to two peristaltic pumps, and also fitted the incubator with a microscopic web cam and a red LED hexagonal array heartbeat inside (to visually add to its liveliness). Next, I built a five-chamber, hand-blown glass bioreactor, as an interconnected body of vessels, tubing, claw stands, and hidden mechanical components.6 Now, I’ve just finished hacking a very cheap 3D printer into a fully functioning (although very moody) bioprinter, controlled by a web interface.7 After weeks of failure, overwhelm and shutdown, through rage, tears, and persistent tweaking, I have finally achieved the ability to bioprint in my kitchen using easily sourced materials—including, of course, my own body fluids. My first print was a clitoris (surprise). This, I am happy to claim, is the world’s first DIYbio kitchen-bioprinted clit.

My kitchen science is not, and will never be a full retreat from the institutional lab. My goal is to continue to write counter-narratives (no pun intended), through the cultivation of a space and community of practitioners, where play with prototyping doesn’t require a swipe card. As I transform my protocols into the vernacular of teaspoons, pots, pressure cookers, and menstrual cups to make living matter with tools I can access and the knowledge I embody, my worldbuilding flows from the places that have long been considered inappropriate sites of origin (see endnotes).

The snake plant in my bedroom bloomed in secret eroticism, scent as a shadowy question in the air. Its botanical gesture is mirrored in the soft petals and stigma-like structure of the bioprinted clitoris. Here, floral and tech converge in a sensory insistence that pleasure, often rendered peripheral or obscene, is central to life-making. This, in part, forms the premise of a new working group I’ve been pulling together:

Obscene Omissions: Female/Queer Pleasure and the Reproductive Blind Spot will be a bimonthly meeting to interrogate the historical and ongoing erasure of female and queer pleasure in reproductive science and technology. My co-convenors are Dr. Gabriela Aceves-Sepúlveda (Simon Fraser University) and Dr. Gabriela García Hubard (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México) who directs @inv_placerysexualidad_unam, a literary theory group to “analyze the representations and expressions of sexual pleasure of feminized bodies.” Other Obscene Omissions participants so far include artist-researchers/ academics based at Transtechnology Research, University of Plymouth. One of the goals of the group will be to organize a collaborative scholarly output, such as a symposium to take place in Mexico City. I invite you to join if this is your area of research and you are interested in participating—please let me know before June 15.8

On the 26th of this month, I fly off to Portugal to participate in a curated exhibition at Cultivamos Cultura, showing a brand new work called Z-stack. I’ll also be giving a talk and workshop at BioLab Lisboa on 3D bioprinting. After that, I return to Ottawa to install my bioprinter as part of a group showcase for the NEW SUNS project at Artengine, presented as part of Pique Festival on June 7. And then, dear friends, I will quickly pack the remaining contents of my material life and move to infamously wet Vancouver. Wish me Frantic Panties luck, as I wish for you in your vivacious endeavours.

Current reading: Deviant Matter: Ferments, Intoxicants, Jelly, Rot by Kyla Wazana Tompkins (2024, New York University Press).

Current listening: Kitchen Witch by Aerial Pink.

Recent inspo: A talk I attended, by Mexican-Canadian artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, at the National Gallery of Canada.

Phantosmia is the experience of ghost smells. I suffered from this for months, one of the symptoms of damage to my olfactory bulb caused by COVID in the early days of the pandemic. For me, it was mostly strong, unpleasant burning smells and it typically woke me up in the night in a panic. I’d much prefer floral phantosmia.

One recent example of this is my inability to order a Hamilton gastight glass syringe to use as my bioprinter extruder nozzle. This $200 specialty syringe can only be purchased through an established laboratory account at a recognized institution.

Certainly, the experience of gestating and birthing a child is not recognized as a biofabrication method, with its own uniquely developed protocols. Instead, it is a wild regenerative process within institutional logics, routinely managed as dangerous and categorized outside the clean precision of hyper-mechanized fantasies of artificial wombs.

I have direct, lived experience with the meticulous requirements of fabricating life. As a mother, I’ve made a human from scratch with my own body, partly as an intentional biohack and partly as a surrender to the reproductive processes my body is capable of performing, according to its own protocols. I spent close to a year culturing an alien hybrid, a responsive experiment requiring adaptations along the way: ingesting acetic acid to soften my bones and free up calcium for the growing fetus, for example. This, along with my carefully designed nutrient mix (my diet) to maintain optimal conditions for growth in the soft bioreactor of my elastic womb, before extruding the human animal through the peristalsis of my uterine and vaginal musculature. In this task, I was subjected to containment procedures based on moralized attitudes towards women’s bodies: the doctor refused to enter the room to tend to my advanced labour and delivery unless I put the requisite hospital uniform (gown) back on; I’d stripped down to my bra because the garment was draping constrictingly around my sweaty movements and adding stress I didn’t need. Said doctor would shortly be putting his hands inside my vagina to pull out a slimy baby, but I’d breached the standard compartmentalization of my birthing body by presenting it as a whole versus a curtained-off section.

This is the actual title of my postdoc research project.

This was a hack build in development at the Pelling Lab (uOttawa), which they later marketed through one of their startup companies.

I commissioned the glass vessels from a Perth-based glassblower, Emma Lashmar. SymbioticA provided me with a ready-made pool pump to power it.

This is a hack build in development at the Alarcón Lab (uOttawa Heart Institute), through their startup company, Intbiotech. They called their first bioprinter hack, “Chihuahua 1” because as Emilio told me, it was “cute but unpredictable.”

This working group is being proposed to the Consortium for the History of Science, Technology and Medicine (CHSTM), with a proposal deadline of June 15.